His singular free form photos have been shown in many of the world’s galleries. For more than 20 years, he has been the head of FAMU’s Studio of Imaginative Photography. We interviewed Rudo Prekop, a Košice native naturalised in Prague, on a unique project that maps the Czech underground community and summarises it in the book Underground / Human Portrait, and on the first Andy Warhol Museum in Medzilaborce that he co-founded.

When you speak to photographer Rudo Prekop, you get the feeling that to him, life is an endless adventure during which he makes his dreams and wishes come true playfully and with ease.

“Originally, I wanted to be an ‘academic painter’. I didn’t really know what the phrase meant but I liked the sound of it. I applied for graphic arts, as everyone else did because everyone wanted to be an artist. There was also a department of photography where nobody would apply because photography was not seen as art at the time. I passed the talent tests, but since the graphic department was crowded, I was admitted to the vacant photography department. Dad took out his old Flexaret camera and said, ‘Come on, let’s go out so you can learn to take pics’”, he describes what led him to his job.

“Everything in life is an accident,” he adds laconically.

Do you remember when, back home in your native Košice, you started perceiving the existence of the underground community in totalitarian Czechoslovakia?

My studies at the high school of technology and art were like initiation for me. In our third year, we made an interdisciplinary exhibition with a few schoolmates. I showed some photographs, graphic artists showed their prints, painters their paintings, ceramic artists their sculptures, and poets read poems. But it was 1977. Any exhibition had to be officially permitted, and we obviously didn’t get any permit, to say nothing of the fact that some of the pieces were so controversial that they couldn’t be shown even today. Case in point: Dano Pastirčák who is a poet, essayist, and very popular preacher of the Church of Brethren in Bratislava today, exhibited his Expulsion from Paradise: a canvas of three-by-three metres in size depicting copulating parrots, roedeer, people, and figures wearing hats with red stars on them and holding police batons in hands. It was called the Expulsion from Paradise and we categorised it as ‘naïve expressionism’.

Just 24 hours later, the state security closed the exhibition and sealed the premises. Our euphoria lasted for one evening. As we were sitting in a pub, I recalled I had left a window half open, so I suggested that we steal the Expulsion. We had drunk a few beers by then, so we intruded the sealed area even though it could get us in prison in an instant, only to find the canvas was too big to take out through the window. So, at least we ‘hid’ it behind the stage where the cops obviously found it easily.

That’s when it all started. Interrogations, expulsions from school. The secret policemen wanted to know where our leadership was. Was it in Prague, Olomouc, or Brno? I said there was nobody: ‘We’re our own leaders.’ They wouldn’t believe me. See, the timing was bad for the exhibition. Charter 77 was just out at the time and nobody thought that adolescent students could be capable of organising such an elaborate exhibit. We predated postmodernism by five or ten years because our exhibition included all forms of fine and literary art, all wrapped in one powerful, authentic, and convincing whole. You could object to anything we exhibited, but the power of authenticity was undeniable. A book about it was published in Slovakia last year, after 40 years – The Forbidden Exhibition 77.

How much did the exhibition’s outcome affect you and your subsequent life?

I got a ‘3’ grade for conduct and conditional suspension; I barely passed the school-leaving exam. As a result, I couldn’t find a job in Košice after school. I was branded as a subversive element.

But then you were admitted to Prague’s FAMU eventually…

One of my high school teachers, Ivo Gil, had some friends at Krátký film Praha, and thanks to him I got a job as an assistant cameraman. And since there was no Internet and the StB in Košice was not in touch with StB in Prague, they lost track of me in Prague. Then I made it to FAMU on my second try.

What sort of world did open up for you in Prague in the 1980s?

I was just a boy with a head full of ideals and I felt like a decoupled carriage. The folks at Krátký film were strange to me – when we drove to locations, they would chat about money or who cheated on whom for hours. In my naiveté, I expected art to be the primary topic. FAMU, however, was a whole other game. The people there were of my ilk and, most importantly, I became part of a group around Ms Anna Fárová. Earlier on, she was the head of the Photography Department at the UMPRUM Museum. When she signed Charter 77, she got kicked out of work, she was no longer allowed to teach at FAMU, they took her passport and I think even her driver’s licence too, and she couldn’t go anywhere, but the StB had no idea of her credit and personality, which drew people from all over the world to visit her. Her apartment in Španělská 5 was like a revolving door for some of the biggest global celebrities – photographer Irving Penn, Norman Mailer, and many more. I became part of that and it was amazing.

They say you had your artistic future mapped out by age 14.

Initially, I wanted to be an ‘academic painter’. I didn’t really know what the phrase meant but I liked the sound of it. I wanted to go to an art high school, which my dad, a medical doctor, couldn’t grasp, but all I wanted to do was paint. I applied for graphic arts, as everyone else did because everyone wanted to be an artist. There was also a department of photography where nobody would apply because photography was not seen as art at the time. I passed the talent tests, but since the graphic department was crowded, I was admitted to the vacant photography department. Dad took out his old Flexaret camera and said, ‘Come on, let’s go out so you can learn to take pics’. So, this is how my photography studies began. Everything in life is an accident.

In addition to your own work, you have been teaching photography to FAMU students for more than 20 years. How does that fulfil you?

It’s good when I feel energy flowing between people. That’s what I really love about it. It shows clearly during the commission exams – you can see that good things energise people and bad things drain energy away. When a poor project is being presented and the author is trying to talk their way out of it, the panel is like dead sleepy, but when it’s good, people are suddenly charged with energy.

Is your photographic vision of the world and your perception of art photography conveyable at all? Can you pass it on to students in any way?

I’m careful to avoid shaping students forcefully to become my followers. All I do is try to help them find themselves, their own core. At their age, people are usually just seeking themselves, so I try to be a companion to them; an advisor who should help them to find their own way and open their creativity valves.

How do you find space to do your own artistic work? Does teaching ever overwhelm you?

It does… And every year, I say to myself, ‘this year is the final one, I’ll quit’. It’s been the same this year… [laughs].

What will you focus on in your creative work?

I always work on long-term projects, I’m a sort of long-distance runner that way. I am in the thick of a project called Kosmos now. It’s about photograms, or photos made without using a negative. I had to put the project on the back burner for a period of time because of the Underground. I let it rest, which is usually good for the project, but I’ll get back to it again.

Interestingly, you were there at the inception of the Andy Warhol Museum in Medzilaborce. Did you just wake up one day realising that you’d like to found yourself a museum? How did it all happen?

Most of my colleagues chased well-paid jobs in the 1990s, yet my friend graphic artist Michal Cihlář and I used to take trains from Prague to Medzilaborce and work on Warhol’s museum in the town of his origins, the only reward being the cost of the train tickets. But it had actually begun in 1987 when Andy Warhol died and his brother, John Warhola, came from the US to Czechoslovakia a few months later. He said his curiosity had beat his fear of coming to a communist country, and he declared on behalf of the newly formed Andy Warhol Foundation that if a gallery or a memorial room could be set up there to commemorate his brother, he as the vice-president would arrange for the loaning of multiple original works by Warhol to be exhibited there. It was a ‘wow’ sort of offer at the time. Actually, it would be a ‘wow’ offer even today. Although the perestroika was in progress by then, everybody was scared. Rumours said in Slovakia: “An American is offering paintings by his dead brother. Who knows what he’s after? Is he a spy…?” The media were more enlightened, so one day Literární týdeník printed an article with the headline Return to Hometown? that described it all. I showed the article to Michal Cihlář and said, we should do something to help the project. And we got engulfed in it. Luckily, the Velvet Revolution happened, or otherwise we would certainly end up in prison, and so we designed, built, and opened the museum in Medzilaborce in 1991. It was the first Warhol Museum to open worldwide. The museum in his native Pittsburgh opened only three years later. I attended the event and the Americans said things like we had beat them by opening our Warhol museum before they did… I think they probably still view us as usurpers from Prague in Medzilaborce, but even so, after the museum opened, people started approaching us with various household items connected to Warhol. They gave them to us, and then I continued collecting in America. As a result, thanks to Warhol, I happened to cover America’s independent underground scene, to which Warhol was a guru, but I felt a debt towards the Czech underground community. In addition, I was always interested in the links between the two cultures.

Where do you see the link between the Czech and the American underground community?

Warhol was an icon of the ‘most American’ style of fine art in the 20th century –pop art – yet he was a Rusyn from eastern Slovakia. The synthesis of the Eastern and Western worlds and the mutual influences are evident. I have this theory that if we asked the hypothetical question of which global artist was the biggest influence on the socio-political developments in Czechoslovakia, the answer could easily be Andy Warhol. Without him, there’d be no Velvet Underground. Without Velvet Underground, there’d be no Plastic People of the Universe, as the band’s founder Mejla Hlavsa confirmed to me: when the famous record with the banana cover was released [one of the most influential records of all times, Velvet Underground & Nico with Warhol’s iconic banana image on the cover], it inspired the formation of the band. Without the Plastic People, there’d be no Charter 77, and without Charter, there’d be no Velvet Revolution of ’89.

It sounds completely logical… Let’s move on to your book, Underground – Photographic Portraits released last autumn, which you started eight years ago. What preceded it?

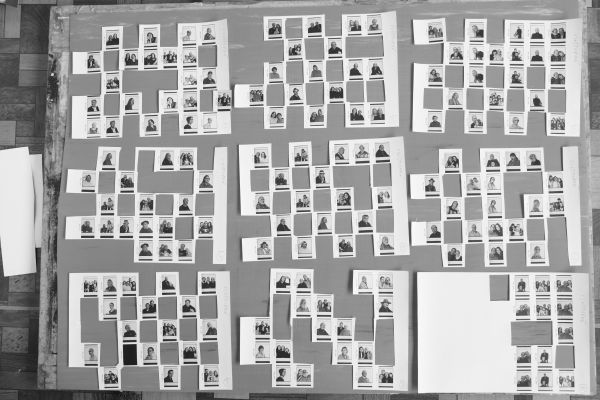

I had it in the back of my mind as this vague plan that I should embark on. One day, I was in a café with Pavel Zajíček, a musician, poet, lyricist, and fine artist as well as one of the most prominent members of the Czech underground community. Pavel said that his daughter Gabriela was coming over from Los Angeles and that his other daughter, who lived in Malmö, Sweden was also in Prague at the time. I said, I should photograph you properly on this rare reunion occasion, and I also suggested to ask Pavel’s dad in Radotín who was 94 at the time. Those were the first photo shoots for the book that builds on photographs and cameos of people from the unofficial culture scene confronted with both their elder and younger relatives. František “Čuňas” Stárek was my supervisor and technical consultant, and he suggested the people and families for me to shoot. When I reached the number 60, I said, enough, or else I won’t get the exhibition done. I did it all in analogue, using a Hasselblad camera, developing the negatives, making proof prints, then doing the first selection, the previews, the second selection, then the big exhibit blow-ups, then the third selection. The result is a travelling exhibition and a book that’s a sort of its accompanying publication.

How many families did you end up capturing?

Sixty-two. It’s not an almanac or catalogue – it’s my subjective selection. Čuňas told me the underground community in the north of Bohemia alone had more than 2,500 members. The people who are in the book are like the founding fathers. I focused on the culture scene because culture will survive us. I don’t remember who the Minister of Culture was two years ago, but do I know what Warhol did in 1962, and that Peter Parler built the Týn Church in the 14th century. That’s why I accentuated people from the culture environment in the book. The Němec family is like the baseline; then the different chapters cover fine artists, musicians, and writers; and then there is the younger generation or second wave of writers, musicians, the Revolver revue, and so on.

You definitely belonged to the underground environment, so you certainly knew everybody involved. That said, who was your biggest ‘catch’?

Even though I approached my friends at first, it was not easy production-wise at all; four production teams worked on it because some of the families are scattered all over the world. In this respect, my ‘rarest trophy’ would be Charlie Soukup who lived in Australian bush for many years. By the way, a TV documentary about him was aired recently, and it showed that even the poorest homeless person was like a bourgeois compared with him. The biopic shows Charlie watering plants in the bush, wearing nothing but a loincloth. When he was to fly to Prague for the premiere of the documentary, it was not certain to the last minute whether they could get him out of the bush and onto a plane. But it worked out fine and, before they took him to the cinema, a production assistant took him to my studio.

Then there are many people who, sadly, are no longer with us, such as Sváťa Karásek, Pavel Brázda, Libor Krejcar, and more…

What do you think makes the book unique?

It is the very first piece of photographic evidence of its kind. Most importantly, it made me realise that time was running out; there was no time to lose because this is all about a generation that is passing away.

While working on the book, did you realise anything about the underground movement that had never occurred to you before? Was there any sort of new personal revelation for you?

I realised that, except maybe one or two persons, all the folks involved in the project were nice people. I had to focus real hard; we would shoot at FAMU in a big studio, with big studio lights, but it was an incredibly nice and rewarding job. I could have gone digital and then have prints done in a minilab, and that would be it, but I really felt like the most time consuming and costliest route was the one to take. Nobody does it like that anymore. I actually retouched the blow-ups, then I reproduced them, in effect digitalising them into print data, which was then fine-tuned in the studio for six months. Right from the outset, my perception was that these people deserved the energy to be invested in it. They are the people who paved the way to a free, civic society in this country, and I am repaying a notional debt to them with this book.